This is the story of my family's successful Sinusitis Treatment using an all natural, easy home remedy. (UPDATE: The treatment worked so well that we all have been cured of chronic sinusitis, and we have been off all antibiotics for over 1 1/2 years.)

Ten months ago my family was struggling with chronic sinusitis that no longer responded well to antibiotics. My oldest son had just been told to get another CAT scan and to prepare for ENT surgery to "open up the sinuses more". We were desperate for something that would help us that didn't involve antibiotics or surgery.

Background: This story started many years ago when we (husband, myself, 2 sons) moved into a house with an incorrectly installed central air conditioning system. We all developed mold allergies and repeated bouts of acute sinusitis, which then led to chronic sinusitis. Eventually we discovered the problem, ripped out and replaced the air conditioning system and all ductwork, but by then the damage was done. Even though antibiotics helped acute sinusitis symptoms which occurred after every cold and sore throat, we always felt like we had chronic sinusitis. Over the years we tried everything we could think of, including antibiotics, decongestants, allergy pills, nasal sprays, daily sinus rinsing with salt water, vitamins, steam inhalation, etc. Both sons even had balloon sinuplasties, which had helped for a short while, but no longer. We had avoided sinus surgeries because we didn't know of anyone who had been "cured" going that route, even with repeat surgeries.

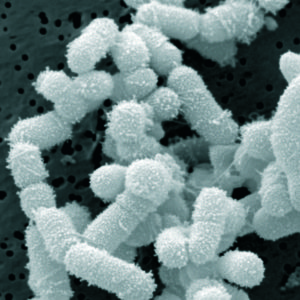

The research: But then last winter I read with great interest all the latest research about bacteria and how all of us have hundreds of species of microorganisms (our microbiome), and how they may play a role in our health. In fact we are more microbes than cells!

Especially exciting was a small study published in September 2012 which looked at 20 patients about to undergo nasal surgery - 10 healthy patients (the controls) and 10 chronic rhinosinusitis (sinusitis) patients. The researchers found that the chronic rhinosinusitis sufferers had reduced bacterial diversity in their sinuses, especially depletion of lactic acid bacteria (including Lactobacillus sakei) and an increase in Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum (which is normally considered a harmless skin bacteria). They then did a second study in mice which found that Lactobacillus sakei bacteria protected against sinusitis, even in the presence of Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum. The researchers were going forward with more research in this area with the hope, that if all goes well, of developing a nasal spray with the beneficial bacteria, but that was a few years away. (Source: Nicole A. Abreu et al - Sinus Microbiome Diversity Depletion and Corynebacteriumt uberculostearicum Enrichment Mediates Rhinosinusitis. Science Translational Medicine, September 12, 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22972842 )

But we were desperate now and didn't want to wait. What to do?

The Experiment: I thought that the answer lay with Lactobacillus sakei (or L.sakei) and I read everything I could find on it. I tried to find a natural and safe source for it, and eventually decided on kimchi. Kimchi is a Korean fermented vegetable product which can be made with varying ingredients, usually with cabbage. According to studies done in Korea, many (but not all) brands of traditionally made kimchi contain L. sakei (as well as many other species of bacteria) after fermentation. It seemed to me that my best bet was to try an all natural kimchi made with cabbage, without any additives, preservatives, and no fish or seafood in it (this last was personal preference). The kimchi brands I bought had to be refrigerated before and after opening. They could not be pasteurized because it was bacteria that I wanted, lots of bacteria. Kimchi fermentation is carried out by the various microorganisms in the kimchi ingredients, and among the bacteria formed are the lactic acid bacteria, one of which can be L. sakei.

In February of 2013 I was off all antibiotics, but feeling sicker (with sinusitis) each day, when I decided to go ahead with the Sinusitis Experiment and purchased several brands of cabbage kimchi (all natural, vegan). Over the next 2 weeks I tried two brands, one after another. Not only did I eat a little bit every day , but I also smeared a little bit of the kimchi juice in my nose, going up about 1/2" in each nostril - as if I were an extremely messy eater. I did this once or twice a day initially. And yes, I was nervous about what I was doing for this was absolutely NOT medically approved. Obviously I did not discuss this with any doctor.

What if harmful bacteria got up in my sinuses and overwhelmed my system? What if the microbes in the kimchi did harm, even permanent harm? What really was in the kimchi? Even if the kimchi contained L. sakei, it also contained many other species of bacteria. The studies said that the bacteria in kimchi varied depending on kimchi ingredients (and each brand was different), length of fermentation, and temperature of fermentation. L.sakei is found in meat (and used in preserving meat), seafood, and some vegetables, but I was nervous about other microbes found in sea food. This was a major reason I avoided any kimchi with seafood in it. After all, the labels on the kimchi I purchased said it was a "live product" (fermentation). When I opened the jars sometimes the liquid inside was bubbling and sometimes even overflowed down the sides of the jar. It takes a leap of faith to put a bubbling strong smelling liquid in the nose!

Results of the Sinusitis Experiment: By the end of the week I found that the one brand worked and it truly felt like a miracle! Within 24 hours of first applying it I was feeling better, and day by day my sinusitis improved. All the problematic sinusitis symptoms (yellow mucus, constant sore throat from postnasal drip, aching teeth, etc.) slowly went away and within about 2 to 3 weeks I felt great - the sinusitis was gone. After a few weeks the rest of the family followed, one by one, in the Sinusitis Experiment. All improved to the point of feeling great (healthy) and have been off all antibiotics since then. All four of us feel we no longer have chronic sinusitis. We are very, very pleased with the results.

It's now 3 years being free of chronic sinusitis and off all antibiotics! Three amazing years since I started using easy do-it-yourself sinusitis treatments containing the probiotic (beneficial bacteria) Lactobacillus sakei. My sinuses feel great! And yes, it still feels miraculous.

It's now 3 years being free of chronic sinusitis and off all antibiotics! Three amazing years since I started using easy do-it-yourself sinusitis treatments containing the probiotic (beneficial bacteria) Lactobacillus sakei. My sinuses feel great! And yes, it still feels miraculous. Some researchers are now testing to see if phage therapy could be a possible treatment for some conditions, such as chronic sinusitis and wound infections. Phage therapy, which uses

Some researchers are now testing to see if phage therapy could be a possible treatment for some conditions, such as chronic sinusitis and wound infections. Phage therapy, which uses

As you may have noticed, I write about the beneficial bacteria Lactobacillus sakei a lot. This is because it has turned out to be a great treatment for both chronic and acute sinusitis for my family and others (see post

As you may have noticed, I write about the beneficial bacteria Lactobacillus sakei a lot. This is because it has turned out to be a great treatment for both chronic and acute sinusitis for my family and others (see post  Big announcement today! The high quality product

Big announcement today! The high quality product